Hansjörg Göritz Studio - Works

Fundamental -

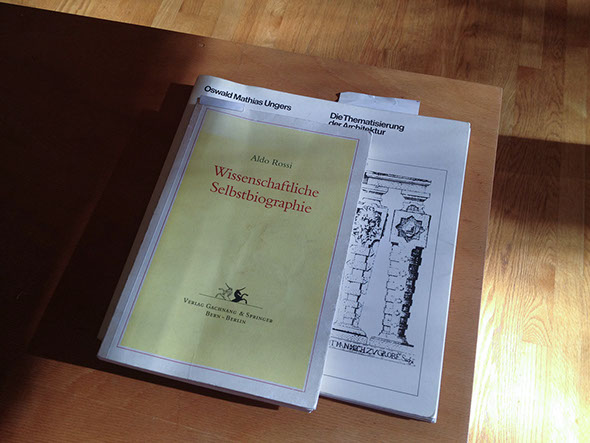

Ungers' Thematization

and Rossi's Autobiography

ex libris - The Power of Books in Architecture

der architekt 6/12

Germany

'From old sources you drink fresh water' is an old Basque saying. It speaks about inexhaustible sources and a refreshing medium as much as it does about the individual involved. This is primarily what makes the power of books inspiring: aforethought words and sketched out imagery. Thus I was overwhelmed thirty years ago by Oswald Mathias Ungers' photographs of stark places and his utterly precise drawings of analog concept partis in my first purchase of an architect's book. To me it was a pleading for a 'Thematisierung der Architektur' [1], - a Thematization of Architecture. Aldo Rossi's 'A Scientific Autobiography' [2] followed shortly after, during my studies at the AA London [3], with its poetically personal descriptions of everyday life and architecture prosaics. Already back then at the AA one was urged to illustrate one's imagination using images. A couple of years later, by recommendation of my friend Thomas Will - who had worked on Ungers' book - I also acquired Rossi's exquisitely made Swiss edition [4]. In conjunction with many more impressively influential books, films, sculptures and imagery, both works became internalized as corner stones and catalysts for what was still to loom as a particular work of mine.

Both were black-and-white expressions of strong teacher personalities that appeared to me in a methodical manner as complementary and yet congenially similar. Ungers prescribes in his view universal depths of works as that are reference points and important to him. Simultaneously he derives timeless as much as surprising themes from these benchmarks.

These deliberations are attentive, catechism-like, sober, nothing less than clinical, chiseled as his own opus. Significantly to him this is not about 'Thematizations in Architecture'; it is about 'The Thematization of Architecture'. The sublime character of his needle-sharp rationalism from north of the Alps relates to the [prospective] architect. I recall how remarkable he states this: 'Transformation or Morphology', 'Assemblage or The Coincidence of Contradictions', 'Incorporation or The Puppet within The Puppet', 'Assimilation or Fitting the Genius Loci', 'Imagination or An Imagination of the World'. Rossi on the contrary, uniquely and poetically describes his personal affinities for the often merely mundane, and in the word's best sense, banal representations of prosaic beauty. Enthused, he shares this perspective from south of the Alps with readers who do not necessarily have anything to do with architecture at all. 'A Scientific Autobiography' just claims to be 'One [...] Autobiography'. The original English title is less pretentious than the German. From this I recall farms in the plains of the Po River delta, the anatomy theater in Mantua, shadows inside the Villa Rosa - long before Zumthor thought of architecture as manifesting in the mellow shine of waxed boards - , the mason whose work holds the energy of his efforts, and also the proposition that by the age of thirty, one should know what to do with ones life. Ungers appears didactically remote, Rossi does authentic self-description by means of his own biography, emphasized by claiming to be scientific. It is only this personal depth that makes his monumental rationalism monumental and grand. Both nearly square sized primers are patinated from browsing, apparently without slipping off into a state of being worn in importance.

What is so powerful and meaningful about it? The influenced beginning of my own track as an architect by both happened at at a time, when in the early 1980s the Internanional Style of Modernism had been declared dead. Powerfully, they made it apparent to me, that at that time there was also a prospective chance to re-discover the mastery of a modern stance. They both illustrated a significant meaning of a non-picturesque context in its many connotations, - related to place, culture and history. Amidst an everlasting flood of appearing and disappearing random imagery prevalent at that time, both were capable of giving me an understanding of the magic of imagination experiencing and anticipating place, and of volume and void as what is lasting. The perception of all those primary experiences was built built in me with timeless validity, qualities that I only later recognized in the spatially rich works within 'Silence and Light' of the great Kahn. Such credo ut intellegam, his simple belief in that order made visible and able to be perceived, could have become key again to making buildings.

In this context of profound grounds and deeper meaning in design, Ungers, by means of a theme, uniquely clarified early on an impetus for my own work. Nomen est omen, - each project was titled to describe its concept and to allow it to be situated in a non-voluntary and non-arbitrary context that is superordinate to the project. Ungers' book laid out the same grounds that his friend Rudolf Schwarz prescribed as 'simply the collective mode, which elevates the individual to nobler community of [...] Common Shapes, discarding all that is artificial, merely fashionable, merely individualistic' [5]. Today it is Chipperfield's curated Venice Architecture Biennale that conjures such Common Ground. Already with Ungers I learned about 'A Puppet within a Puppet', 'A House within a House', 'A City within a City', and all the other other themes, yet also I learned about a theme and its meaning. Those appeared to me as real impressive, simple and comprehensive archetypes of spaces in which all mankind at all times could concur and be in accordance with, to even build upon and extend. Later I catch myself with the theme 'The House is The Garden is The House is...'

Still unconsciously, it appeared to me back then that Ungers - despite profound reasoning of his own works with reflected themes - at the same time 'depersonalized' for the sake of achieving universality. Rossi on the other hand seemed to recommend acknowledging that any impressive work is created by personalties anyway, and that the creator's spirit is captured in their creations. Consistently 'autobiographically', hence individually and subjectively, he describes the objective that is universal to him as 'scientific'. Ever since reading Rossi, I have only considered as truly biographical and as knowledge something that was long and deeply experienced. This is also what was common to both authors.

Hence both of theses highly educated educators are in the rank of encyclopedists. These chroniclers and their wonderful books deserve again to be used bu those who are usefully inspired. Ungers' academic and Rossi's non-academic style of educating were a strong impulse. During the era of Inter Rail and print media such imagery and writings made the world look large and grand. They made a thirst for traveling and experiencing the world as an actual extension of the lecture hall. The occurrence of such an allure from a mere description that one is drawn to the place and into the space makes us recognize that space is actually indescribable. In the post-paper era, where now Google is taken by many as a substitute to evoke this formative experience and to inspire, this power of book is an unheard-of or unseen lesson.

Today, myself being the age of that these two authors were back then, the once inspiring spirits of these and other masterminds probably have lost some of their initial and personal importance. However, despite the path now being my own and being an open-future track, such is the way it profoundly prepared in the beginning. To pass this on is of utmost pleasure, - to inspire my students myself, - to see them bring expressive and memorable books to the studio, - and to witness them travel to powerfull places. I only like go to important places and spaces myself. Next spring, after precisely thirty years I will go back tho the Eternal City, with the honor of a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, to verify if Ungers and Rossi and Kahn were right, and whether contemporary works - with all its figurative inflation - can still rise to the level of the exemplars and lessons of the books, when it comes to evoke the profound and to get inspired for the timeless.